CREATIVITY WITHOUT THE MYTH.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”

So says Prospero in The Tempest, grappling with a world that refuses to bend to his will. He has a vision, no doubt, but the journey is chaotic, riddled with surprises and shaped by the unpredictability of others. And truthfully, launching a new product in today’s saturated market feels much the same. Everyone’s got ideas, slick branding, and clever slogans. What sets you apart isn’t just what you offer, but how you think.

That’s where creativity enters the picture.

Now, let’s not get romantic. Creativity isn’t some ethereal gift that floats down from the heavens onto a chosen few. Long gone is the myth of the lone genius. As early as the 1970s, scholars like Nyström began shifting focus from creative personalities to the creative process — a series of stages through which ordinary people can produce extraordinary ideas.

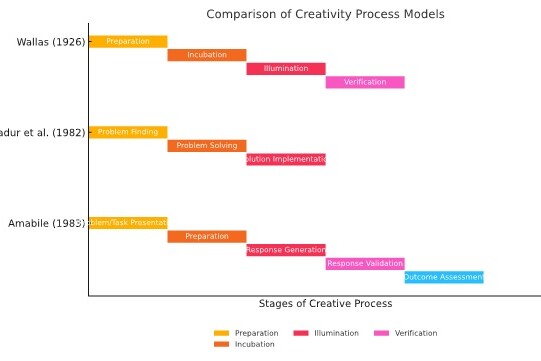

Wallas (1926) proposed one of the earliest models: a four-stage process of preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification.

First, there’s preparation, where we refine our goals and dive into research — reading, observing, collecting ideas from every corner we can find. It’s about equipping ourselves with enough knowledge even to see the problem. In a business context, this might mean customer interviews, competitor analysis, social trend monitoring — anything to broaden the mental map.

Then comes incubation — the glorious act of doing nothing (on the surface). The brain steps back from the task at hand, but behind the scenes, unconscious processes are sorting through all that prep work. It’s the bit where ideas ferment. Sometimes a walk, a nap, or a scroll through memes is precisely what the process requires.

Illumination is that spark — the sudden “a-ha!” when things click into place. It’s usually unexpected, often inconvenient, and rarely perfect.

That’s why we follow it with verification, the stage where we test our shiny new idea against real-world criteria. Can it work? Does it solve the problem we set out to tackle? If not, it’s back to the drawing board (or more precisely, back to preparation).

Other models build on this. Basadur et al. (1982) describe creative problem-solving as a cycle of problem-finding, problem-solving, and solution implementation, emphasising that how we frame the problem is just as significant as how we solve it. And Amabile’s (1983) five-stage componential model reminds us that motivation plays a central role; people do their most creative work when they’re genuinely interested in the task, not just ticking boxes.

Across all these models, one thing is clear: creativity is a form of work. It’s effortful and rooted in both individual insight and social context. It thrives in environments that encourage flexible thinking, risk-taking, and collaboration. And crucially, creativity alone isn’t enough; it must give way to innovation, the process of turning those ideas into products, services, campaigns or systems that bring value.

So no, creativity isn’t just about brainstorming over croissants or posting vague mantras about “thinking outside the box.”

It’s a structured dance between logic and imagination, knowledge and intuition, experimentation and evaluation. It’s what makes the difference between a product launch that flops and one that revolutionises the market.

In that sense, we’re all a bit like Prospero — trying to conjure meaning and control from a swirling storm. The path may be murky, but with the proper creative process, the right questions, and a willingness to follow the ideas where they lead, even the most unpredictable journeys can yield spectacular outcomes.

References:

Amabile, T.M. (1983) The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), pp.357–376.

Amabile, T.M. (1988) A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, pp.123–167.

Basadur, M., Graen, G.B. and Green, S.G. (1982) Training in creative problem solving: Effects on ideation and problem finding and solving in an industrial research organization. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 30(1), pp.41–70.

Dawson, P. and Andriopoulos, C. (2021) Managing Change, Creativity and Innovation. 4th edn. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Nyström, H. (1979) Creativity and innovation. Chichester: Wiley.

Wallas, G. (1926) The Art of Thought. New York: Harcourt Brace.